Download the PDF on Academia.

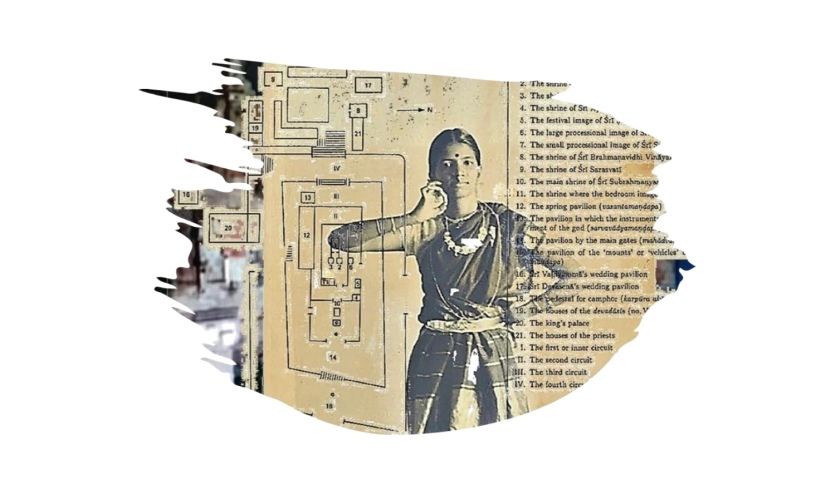

June 20, 2023 / Dr. Saskia Kersenboom

“What is there? It is all gone; it will never come back. Nowadays, anyone can do anything on stage or in film. We were God-fearing. After we had got our status as devadasis, we could decide for ourselves. If some were deserted by their men, we still had our profession which afforded us a living. We had our own discipline”

—Smt. P. Ranganayaki (1914-2005)

This was Ranganayaki’s answer to Saskia Kersenboom’s question “whether the Devadasi Heritage will ever come back”. In her essay, Kersenboom recollects the voice of her devadasi teacher as she narrates her family tradition, life, and dedication to the Murugan temple in Tiruttani as well as the tragic rise and fall of the devadasi tradition.

Reflections on the Classical Ballet La Bayadere, (premiere 1877, St.Petersburg, Russia)

Aiyyooo – my mirror cracked: it cracked once, it cracked twice, and now it cracks a third time! How long can we ignore these ruptures in our image? Do our eyes still meet or do we disappear in the abyss of the cracks? How long do we persist in using an object so familiar, so present throughout a lifetime: every day getting up, preparing for a world to unfold itself, to participate in, recognizable to others and thereby to ourselves? Can we glance at this broken image in the evening and embrace deep sleep… a sleep… that dissolves all attributes?

We lost our livelihood, our profession, our right to perform our songs and dances in the temple… Our family has lived behind this temple for more than four generations. This mirror has seen us all. Together with the priests and our musician colleagues, we take care of the temple, the gods, the devotees, and of course of our king. The priests live opposite the temple tank, we, and the musicians on the other side; they can continue but we devadasis ‘servants of God’ cannot. On November 26, 1947, three months after India became independent, this Indian Government issued the Devadasi Act. It forbids the dedication of women to a temple, to perform their ritual song, dance, and other tasks in daily and festival worship. We can stay in our house but no longer participate in any ritual. If we do, we will be fined 500 Indian Rupees or six months imprisonment.

How could this happen?

I was dedicated to the temple as a child, as were my grandmother and great- grandmother. We hold the hereditary ‘right to perform’. An application for my admission to temple service was signed by ten elderly devadasis and priests prior to being sent to the King. The King is the ultimate authority over our temple and several other temples in this region. Such an application takes six months. My grandmother trained me in vocal music and dance, while a traditional scholar taught me reading, writing, recitation and memorisation of the ancient legends of our gods. Once the application was approved, my maiden dance performance was celebrated in a private function by tying the customary dance bells. These anklets turn a dancer into a musician…every step of that performance was not only seen but heard as well! They opened the door to my ‘marriage’. Devadasis are not married to a mortal husband but to one of the god’s weapons. In my case, Murugan’s dagger was brought to our house; there my marriage rituals were conducted. The next day, my family, well-wishers, and the priests took me to the temple with all ritual and musical pomp to perform a full dance concert in front of God. In conclusion, a ‘Trident Emblem’ was burnt onto my arm by means of a hot iron. This ritual is called ‘marking’ and allowed me to perform the Kumbharati ritual for the first time. More about that later.

We believe that our world is just one of Triloka ‘three worlds’, namely that of Gods, Mortals, and the Nether Regions. Sometimes gods and goddesses manifest themselves spontaneously, as a miracle stone or tree in the field, or as an anthill where a snake has taken its abode. In a temple, the gods live here, right in front of our eyes. It is by their goodwill that they descend into a statue that was made by human hands. Priests know the procedures for inviting gods into the world of mortals, to establish them there in such man-made form, be it stone, bronze, or other metals. It is our duty to take care of this divine presence so that the gods do not leave and are accessible to devotees. Our songs, dances and rituals serve this purpose. Ritual manuals, stone inscriptions, sculptures, and paintings on the temple walls record our presence for over a thousand years.2

What went wrong?

This is a long story that I heard from my grandmother and great-grandmother. In those times foreigners called us Bayaderes; people say it means ‘dancers’ but we are so much more! I suppose they chose this word because they encountered devadasis only outside of the temple. The inner sanctum is not accessible to non-Hindus. Daily rituals are performed inside, but processions, festivals and royal performances are open to all or by invitation to the palace. So how could they know?

Our participation in the temple practices follows ritual time that runs in cycles of the day-and-night, week, month, seasons, and year. Rituals attempt to establish Mangalam ‘happiness, welfare, auspiciousness’. In concrete terms our day looks like this: early in the morning, before sunrise, we get up, have our bath, and go to the temple. At the main entrance my grandmother used to sing a ‘Wake-up’ song. In my time we sang this only in the dark month of December-January. After the priests have initiated the daily routines we sing a Praise song for the Elephant-headed god Vinayaka followed by ‘Happiness!’ songs for the various gods on the temple ground. Noontime allows the gods to take a rest. By four p.m. we are back. The priests prepare the gods for the afternoon worship followed by our songs to establish their wellbeing. So far, every part of the day was ‘safe’, lit by ample sunshine. But, by dusk darkness sets in. This is the time when anti-gods gain strength and emerge from their Nether Regions. Now the ‘core-competence’ of a devadasi is indispensable. Weapons of the gods evoke the Goddess, they represent her power to protect life against, illness, decay, and death. Another manifestation of the Goddess is the ‘Waterpot’, the Kumbha that resembles the womb of fertile women, its embryonic waters and growth of new life. On top of this waterpot a lamp is lit. We rotate this burning Pot-Lamp three times clockwise along the icon of the gods; this ritual is called Kumbharati. Fire burns away all negative energy emitted by the anti-gods. Their ‘Evil Eye’ drains the vitality from its objects of envy. Devadasis can counteract such forces. Being married to the Dagger, merged with the power of the Goddess, holding the kumbha pot, her ritual cleansing by burning fire guarantees the efficacy of life over death. All other gods on the temple ground receive such ‘cleansing’. Finally, God and his goddess are ready to retire. His goddess is waiting on the swing while priests carry an effigy of Murugan to the bedchamber. Devadasis accompany them and celebrate the divine ever-green, daily reunion by a lilting Lullaby.3

Temple festivals take the gods to public spaces. Outdoor processions allow all devotees to get close and see their gods. Such festivals may last from eight to twenty- seven days. It all starts in deep secrecy during the night when local soil is dug up to plant the seeds of the festival and a tree is selected to provide a pole for the festival flag. Demonic forces that inhabit the processional route are propitiated and pacified by various offerings. After that, each day has a specific theme that highlights ancient and local legends. The god rides different mounts like a ‘ram’, ‘lion’, ‘swan’, or ‘peacock’ figure. He travels in a palanquin, on a float or goes for a hunt. All journeys are accompanied by devadasi song, dance and Kumbharati. Highlights of the festival are the procession on a huge chariot that is pulled around the temple by his devotees. Murugan’s marriage to one of his two goddesses is next. Devadasis acted like bridal maids, attendants to the wedding ceremonies and as go-between to Murugan and his ‘other goddess’ who slams the door of her shrine on his return.

In the times of my grandmother and great-grandmother festivals set huge artistic challenges. Devadasi songs and dances caught the eyes of the Indian public but also of the foreign visitors or residents. They reported on our ‘Stick-dances’, ‘Boat-songs’, ‘Operatic Dramas’ and Atta Kacceri ‘Dance Concerts’. My grandmother wrote down our family repertoire of more than 140 compositions in the Telugu, Sanskrit and Tamil languages. Her manuscript comprises ritual song and dance, concert repertoire, songs for social events and comic songs. As times changed devadasis received dwindling support; thus, I inherited and performed only part of this huge repertoire.4

Power broken

We feel that a harmonious Indian life can be maintained only on Indian soil; to cross the oceans is dangerous and contaminates the traveler. On return, such influences should be ritually cleansed. Yet, my great-grandmother and grandmother saw a steady increase of Indians returning home from studies in the West. —It changed them irreversibly.

For us the temple, the gods, the king, and his palace are all inter-connected into an ‘auspicious life’. During daily and festival rituals many songs and dances address the god and the king in one breath, nourishing their Shakti, ‘divine power, protection, love of the land, its people, and all sentient beings’. Our king used to visit our temple festivals, holding court in his own quarters on the temple ground. During the festival of Nine Nights in celebration of the Goddess, we used to travel to his Royal Palace. There, we offered a Dance Concert to celebrate his Victorious Reign on the tenth, concluding day.5

Foreign returned Indians lost sight of our beliefs and modes into a happy life. They proposed new concepts like ‘Spirituality’ – an English term that we could not understand. Our requests to translate this alien ‘aim-of-life’ into any Indian language term met with no response. Yet, their convictions and foreign alliances started to affect us. Our temple could maintain traditional values until Indian Independence in 1947, but others wavered and became embarrassed about many aspects of temple ritual, especially devadasis. Some kingdoms were annexed by the English like the Royal Court of Tanjavur in 1856. Some others replaced devadasis by wooden dolls spinning around on the temple chariot.

Blurred horizons

My great-grandmother told me about ‘what foreigners think of us’. In 1877 the Emperor of Russia commissioned a grand Ballet called ‘La Bayadere’. A Russian poet wrote the story, a French dance master created the choreography and an Austrian musician composed the music. Even earlier a German poet composed a poem called ‘The God and the Bayadere’. Both works told about a devadasi. Yet, nobody saw us, heard us or talked to us. We were very upset. Why? Because they all died…It was all very inauspicious, such violence and tragic death of the bayadere, the destruction of the temple, the king, his daughter, and her husband by the gods and then they continued their journey in the Nether Regions.

Incredible…!

We are concerned about Life and do not idealise Death; that is what Mangalam means: ‘to move like a river, gain strength and transform life in the direction of well- being’. In society we assist at Samskaras ‘Rites-of-Passage’ such as protecting pregnant women, naming newborn babies, entering a new home, and singing songs while pounding rice.

Most importantly, we officiate at marriages. A married woman is called su-mangali ‘she who abounds in auspiciousness’. Her life may flourish into the joy of a husband, love, children, a home, and an extended family. Our presence at her marriage brings ‘good luck’ to both. Devadasis are not married to a mortal husband but first to the Goddess (through the Dagger) and then dedicated to a God who will not die. Therefore, a devadasi will never be a widow. She is not only a su-mangali but a nitya- su-mangali ‘a woman whose auspiciousness is guaranteed, ever-lasting’.

Foreign ideals of celibacy of priests and nuns are not for us. Human life goes through stages of a child, a student, a householder and finally when our hair turns grey of an ascetic. In our temple priests must be married – if not his sexual heat will affect the gods. Even the gods are not celibate, on the contrary they have many wives, and delight in lovemaking. Devadasis embrace a full life and are allowed to have children; not as a ‘first wife’ because that place was taken by her ritual marriage and dedication to the temple, but as additional wives. Before 1947, India was never monogamous, a householder or king could have several wives, provided he could support them. Our status as Nityasumangali made us welcome assistants in wedding celebrations: we decorated the marriage pavilion, prepared the wedding necklace, sang ‘Happiness!’ songs to the bridal pair and danced love poems that evoke the Bliss of the Divine Wedding of our God Murugan and his Goddess Valli.

In the past, priests provided the ritual structure while we created the ‘Taste of Life’. Now, that taste has run dry… like… our own lives…6

A mirror frames the time and space that we inhabit,

its furniture, and decorations; in short, the very

stage-props for the scenario of our life.

Do these attributes still ‘fit in’, despite the cracks?

What clock ticks away the time, does it run ‘in time’

to fit the right timing? When do we discard

a broken mirror? Anyhow, is a new one available to us?

—

NOTES

1. Kaveri ‘River of Life’, photo credits: Thomas Voorter. Please access the scrolling video in the YouTube link for a reading of the scroll and listening to Ranganayaki’s topical songs. Kaveri ‘River of Life’ is a supplement to the Essay Der Sprung im Spiegel, published by The Bavarian State Ballet, Munich, Germany (https://www.staatsoper.de), at the occasion of their Retake of the Ballet La Bayadere, 2023.

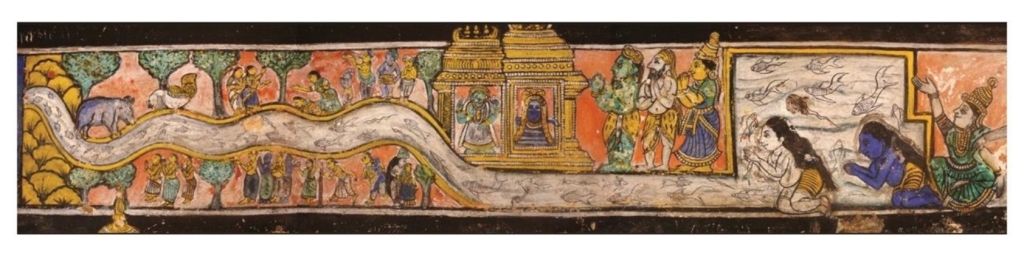

This (partial) mural in the Pancanadishvara Shiva temple at Tiruvaiyaru dates to the period of Maratha Kings of Tanjavur (1674-1855CE). Folk wisdom has it that a place without a ‘Temple and without Flowing Water’ is not suited for human habitation. Rivers are goddesses, the vital source of life. Kaveri, Ganga, Sarasvati are all females of divine origin. Ganga descended to the earth from Shiva’s matted locks, Sarasvati is the goddess of learning, the performing arts; she embodies Saras ‘fluidity, flexibility, vitality’. Kaveri was brought down to South India by sage Agastya in a large pot. In Tiruvaiyaru Shiva is celebrated as Pancanadishvara ‘Lord of the confluence of Five Rivers’. The mural celebrates the Mangalam ‘auspicious character’ of this unique location: the flowing river guarantees the fluidity, ever moving, ever transforming quality of LIFE. As such, the ‘auspicious river’ supports the basic values of the temple: growth of nature, human wellbeing, power of the gods and king who protect against draught, decay and evil forces. In this Essay the River Kaveri is a powerful metaphor for the essence of devadasis who were rooted in the same logic of the river goddesses. In Tiruttani, the devadasi street was dominated by their temple to goddess Sarasvati for whom they were cala-devi ‘walking goddesses’. The Kaveri River combines all aims of life and of life support by devadasis in the temple, court, and society. Unfortunately, the metaphor works the ‘other way’ as well. When Independent India decided to abolish the relevance of Devadasi Labour in 1947, it overlooked the holistic power of the river as the source of life as well. The Hindu Newspaper (Business Line), 2021, reports the results of extensive research on today’s quality of the Kaveri water: arsenic, zinc, chromium, lead, and nickel were found as well as pharmaceutical contaminants, anti-inflammatory drugs, anti-hypertensives, enzyme inhibitors, stimulants, antidepressants, and antibiotics.

The Kaveri River still flows to sea and enters the Bay of Bengal at the temple town of Chidambaram, but at which price? Modernity dried up Devadasi relevance, does it dry up nature as well?2. Listen our song Devudaura. See YouTube link above at 0:20-1:15.

3. Listen to Kumbharati rituals. See YouTube link above at 1:25-2:20.

4. Check the Webinar ‘Devadasi Literacy’ on the family heritage of Ranganayki’s grandmother (1871-1950) as attested in the Subburatnamma manuscript. YouTube link below:5. Listen to Curnika...’Eulogy’. See YouTube link in note 1 at 2:25-3:05.

6. Listen to Shobhanam...’Happiness...!’ See YouTube link in note 1 at 3:13-4:50.About the author

Dr.Saskia Kersenboom studied Indian languages and Theatre Studies at Utrecht University, The Netherlands. Parallel to this academic curriculum she trained and performed devadasi repertoire from temples and royal courts in South India, Tami Nadu. This resulted in her PhD Nityasumangali (1984) that was published as Nityasumangali – Devadasi Tradition in South India, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1987-2020, 6 editions. Saskia Kersenboom has developed this intersection of Performing Arts and Academic Studies further as Associate Professor of Linguistic Anthropology and Theatre Studies at University of Amsterdam (1990-2013). Her work includes Guest Professorships at Conservatoria for Dance in Europe, USA, and India. For the Internationaal Danstheater she co-produced the evening-filling Ballet ‘Mother India’ that toured both in The Netherlands in India. She was Co-Curator at Museum Rietberg, Zürich, Switzerland to the major Exhibition Shiva Nataraja (2008). In 1994 she founded Paramparai Arts to foster Devadasi Heritage through UNESCO Consultancy, cultural programs, long and short courses in Hungary and India. For further information: https://www.paramparai.eu.

Copyright

All Rights Reserved © 2023

Paramparai/Dr. Saskia Kersenboom

Publisher:

Sathir Dance Art Trust (est.1995)

All content on this platform, including text, graphics, logos, images,

videos, and audio, is the property of the rightful owner.

Unauthorised use or reproduction of any content without

prior written permission from the owner are strictly prohibited.

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of the publisher. From our website, you can visit other websites by following hyperlinks to these sites. While we strive to provide only links to useful and ethical websites, we have no control over the content and nature of these sites and the links to other websites do not imply a recommendation for all the content found on these sites. Please also be aware that when you leave our website, other sites may have different privacy policies and terms which are beyond our control.