All Rights Reserved ©2021 Sathir Dance Art Amsterdam Chennai. All content in this article: the text, photos and videos is intended for personal use only and not for commercial purposes. The content on this website is entirely copyrighted to: Sathir Dance Art Trust and solely owned by the publisher/provider of the content. Unauthorised republication in any form is strictly prohibited without prior written permission of the publisher. Disclaimer: the views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of the website.

Viewing Dance On Your Device? By Lakshmi Viswanathan

The highly exalted (by some) Chennai Music Season comes and goes like the proverbial Indian monsoon. Sometimes there are storms of excitement, and at other times there are disconnected murmurs of ennui and the lack of novelty. One does not have to, as is generally customary, blow the trumpet about how great this mammoth event is, how the numbers have multiplied to such an extent that records are broken every year as to how many sabhas are holding festivals, and how many titles are given (or taken) and how many brilliant youngsters are competing for a “slot”. —Dance (Bharatanatyam) has had a rather slow start in the 20th century as it was considered the stepchild of the music season. Chennai got the UNESCO recognition for a city of Culture specifically for music. Not dance.

Starting with one dance festival with one conference on dance and one title (by Krishna Gana Sabha from the seventies), dance has edged its way to become many city-wide ‘festivals’, simply because the supply was too large and dancers even from as far away as New Delhi kept their “Mission Impossible” relentlessly active at the doorstep of the inscrutable sabha secretaries who wielded that magical power to give them a “chance”. Like a satellite landing on another planet after a risky flight, dancers kept their focus on the Chennai season to end up cutting the pages from the local newspapers splashed with their pained expressions in living colour to add spice to their scrap books. Bio-datas, and listing in the Chennai sabhas, became, over time as important as adding that dash of essential turmeric to a rasam.

The harvest of shows, lectures, and titles have sadly petered out with the unexpected global pandemic, just when our singers and dancers were loudest in claiming that they were “global” artists. Sadly, they all face an uncertain future, while displaying those inimitable expressions of deep anguish immersed in tears shed at the feet of Lord Nataraja at Chidambaram. One feels like sending them a message of solace, hope and forbearance. But the exercise would not have any effect because the all consuming passion to perform has become an all consuming age of doubt. The valiant effort to film dance to console the mood of desperation is the only ray of hope. “I will miss the audience”, “my heart aches not to hear applause”, “I am sweating it out to make it authentic”, “I miss my travels”, “I hope things will change”…the whispers of agony go on.

Let us examine the streaming of live dance performances first. Recently I danced to a live audience for ABHAI’s “Nritya Prakasam” Deepavali dance festival. It was streamed for viewers simultaneously. Knowing the experienced Chella Vaidyanathan I requested him to use two cameras to, first, prevent a monotonous visual; and secondly, that my facial expressions (I presented forty minutes of five Abhinayam pieces) are clearly recorded. Next I told Gayatri, my makeup artist, to understand I am dancing for the cameras and a small audience…so, keep the makeup ‘light. And not to exaggerate the eye makeup. Next I requested Murugan, the stage lighting person not to create shadows and colours which will put the cameraman in a quandary. The result was quite satisfactorily achieved for a low budget event with no rehearsals on stage.

With the new digital cameras I see that several amateurs are making interesting visuals. On YouTube some dancers have posted garden and terrace performances that have been filmed rather well in spite of the dances and the dancers leaving much to be desired. Some Instagram regulars have flooded the market with impressive videos of their dance with exotic lighting. I do not want to discuss the quality of video dances which I get regularly from my friend Mark Morris. His groups are filmed by experts whom we cannot hire!

Let me share my filming -dance- experience of 1987/88. Being true to my adventurous nature, I embarked on a project to make a documentary about Bharatanatyam. Having the project supported by the Festival of India, with a decent budget helped. All I wanted was the best cameraman, because I had my script, my own selection of dances from my repertoire, and additional dancers to fill the screen. I literally surprised the national award winning cameraman Ashok Kumar by visiting him with this idea. He rose to the occasion in his inimitable way. We must film in 35mm he said, rejecting the widely prevalent videography of the time. Thus started my most challenging tryst with filming dance. It was not easy because I had to rethink some of my notions about film under the guidance of Ashok Ji. He had to convince me first that we cannot do all the dances indoors like a proscenium stage performance. I was then made to go through every stage of the production as a learner. Ashokji’s first request when he knew I was going abroad for some shows, was to give me the name of a speciality shop in London, and a list of camera lenses which he assured me were absolutely necessary to film dance in an aesthetic way. After this I decided that all technical requirements were in his hands, and I will be guided by him. Music was recorded for the entire film of fifty minutes in the sound studious of AVM. I got the correct makeup materials from an exclusive shop in Covent Garden, London.

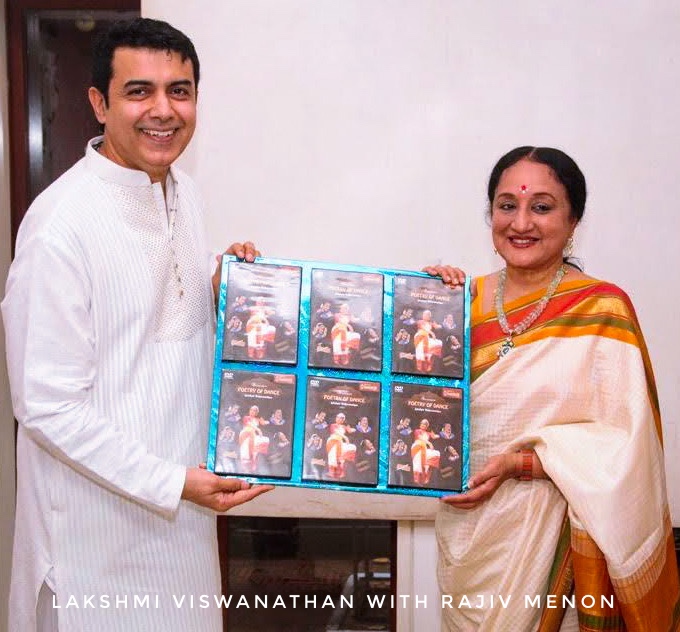

From the initial scenes of a dance class shot in a typical traditional house, to the shooting of ‘Krishna Nee Begane’ in the lush greenery of Ooty, and the shooting of the sculptures of Chidambaram temple to ‘Shiva Tandavam’ in a studio to the Thillana in Ekambareswarar temple in Kanchipuram, it was a roller coaster ride. I insisted that my Varnam be filmed in a hall, with a décorated backdrop to simulate a stage. Ashokji tested my patience at every stage of the filming. Lighting had to be rearranged frequently as the camera moved to shoot the dances from different angles indoors. Several takes meant I had to pick up where I left and dance again from the start of each segment. What worried me was how I would bring that verve and spontaneous movements which are the hallmarks of my dance. I learnt as I went along. The most difficult part was to sit in the old editing room to sync the dance sequences with the music and choose the best takes to put it all together. A laborious task – is an understatement. The end result: my film, the POETRY OF DANCE is one of a kind. When I asked Rajiv Menon, the expert director and cinematographer to release the DVD version, he was blown away by the film. That we did it when we did it, and the way it turned out, amazed him.

The reason I am chronicling this adventure of mine is to emphasise that with digital cameras and with a whole new generation of camera experts, filming dance today should be a cake walk. Probably the sabha aficionados are keen to make viewers today feel that they are actually in the sabha, uncomfortable seats excluded, and are watching their usual seasoned dancers melting in ‘Bhakti Bhava’. Fine, so be it. But surely one can take advantage of technology and use three cameras to capture all the nuances. One can even use the most modern cameras which can move with the strides of the dancer. I have seen dancers filmed from different angles and perspectives. Editing is easy, they say. So why don’t the dancers change costumes choosing different textures and colours. Above all, I really wish the dancers would consult the make-up artists of the cinema industry to tone down their face, and make it suitable for cinema, watch those wigs and hair extensions, take a break while shooting, to mop up the sweat…..one can go on.

Well, one can only hope. In the name of tradition, Madras gets stuck with ideas which are outdated and in the end, boring for the viewers of dance. Unless there is proper collaborative involvement of the dancer/choreographer with producers, directors, technicians, and editors with digital filming experience, and most importantly, have a working knowledge of dance (bharatanatyam, in this case) are put to use, dance lovers will have to bear the monotony of the streamed performances, popcorn in hand.

END

‘Nritya Kalanidhi’ Guru Lakshmi Vishwanathan is a renowned Bharatanatyam artist, scholar, writer and mentor. She is well-known as a performing artist and choreographer of group productions. She is equally well recognised as a writer, having authored four well acclaimed books, contributed to journals, newspapers as well as dance portals. Her lectures and demonstrations as well as Master classes erudite, informative, and popular with dance students everywhere. She is currently the editor of the Kalakshetra Journal.

All Rights Reserved ©2021 Sathir Dance Art Amsterdam Chennai. All content in this article: the text, photos and videos is intended for personal use only and not for commercial purposes. The content on this website is entirely copyrighted to: Sathir Dance Art Trust and solely owned by the publisher/provider of the content. Unauthorised republication in any form is strictly prohibited without prior written permission of the publisher. Disclaimer: the views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of the website.