Amsterdam, September 2008 / By Jeetendra Hirschfeld

NOTE:

Sathir Dance Art Trust © 2008-2023

All Rights Reserved.

Reproduction, in part or in whole, of the essay, text, photos, and videos is strictly prohibited without prior written permission from the author.

Introduction

Many years ago, my teacher Rajamani shared with me fascinating stories about a famous dance svarajathi called ‘ē mandayānarā’.1 These anecdotes were passed down to her by Meenakshisundaram, a renowned dance master from Panthanainallur. The central figure in these tales was Tanjore Gnyana, a highly skilled courtesan dancer who possessed remarkable abilities not only in dance but also in singing and playing musical instruments. Gnyana captivated audiences with her expressive movements and earned great respect from even the esteemed nattuvanars of Tanjore. One significant event in Gnyana’s life was her performance for British Royalty. Alongside her nattuvanar, Mahadeva, she dedicatedly prepared for days to showcase the composition of ‘ē mandayānarā’. Gnyana travelled to Madras, where she had the privilege of dancing before the prince. The prince was so impressed by her talent that he lavished her with valuable gifts, propelling her to fame and establishing her as a prominent figure in her profession. Her success even served as an inspiration for other dancers, motivating them to learn the svarajathi in hopes of one day having their opportunity to perform for foreign royalty.

In Rajamani’s apartment, I noticed a small framed picture of Gnyana, which I was allowed to make a copy of. This piqued my curiosity, but at the time, I did not delve deeper into Gnyana’s story. It was not until years later that I stumbled upon a passage in William Howard Russel’s book, “The Prince of Wales’ Tour: A Diary in India” published in London in 1877. This passage mentioned Gnyana’s performance for Prince Edward of Wales during a reception at the Madras Royapuram Station. Excited by this discovery, I sought more references and found additional information in J. Drew Gay’s book, “The Prince of Wales in India.” Also published in 1877. Furthermore, I came across several newspaper clippings that discussed or reviewed Gnyana’s captivating presence at the Royapuram event.

A slightly different version of this essay was initially published on sathirdance.blogspot.com in 2006. Figure III added in 2016. Download the complete essays on Academia website: PDF

Figure I: Tanjore Gnyana (1857-1922)

The Prince of Wales’ Tour in India

His Royal Highness, Prince Edward of Wales, travelled extensively through India in late 1875 and early 1876. The Prince and his suit first set foot on Indian soil in Bombay (Mumbai) on a bright and sunny morning, Thursday, November 8th.

His Royal Highness arrives in Tamil land late afternoon on December 9th, from Ceylon (Sri Lanka) by boat to Tuticorin. In the morning, His Highness travels in the first passenger train from Tuticorin to Madura, making stopovers in one town to another before reaching Madras city on December 13th.—On Monday morning, December 11th, the Prince stops to visit the magnificent Meenakshi Sundareshwarar Temple, and later in the day, there is a visit to the Ranganathaswamy Temple in Srirangam. These visits are the first encounters His Royal Highness has with devadasi dancers.

At the Meenakshi temple, the Prince encounters a band of dancing girls, who—“scattered flowers before him, fillets of gold and silver tinsel were placed on his brow and arms, richly-scented garlands were brought in baskets and were passed over his shoulders.” (Russel, 308).

And later in the afternoon, he visits the Thousand Pillar Mandapam of Srirangam.

“At the pagoda, the Prince was received by the dignitaries of the temple with all possible pomp and show, accompanied by a number of nautch-girls, gaudily dressed, ornamented with spangles, rings, jewels in their hair, and wreaths of flowers on their heads, met the Prince at the end of a long corridor, and conducted him to the temple, the girls singing a low chant, and Mattering flowers on the pathway.”

“All was not over, for a portly priest, whose eyes twinkled with delight at having been introduced to the Prince, proposed that the girls should dance in honour of the occasion. Whereupon they began the low chant and curious shuffle, which I have already described. There was a conspicuously ugly man who sang, or, to be more just, howled vigorously. There was a piper, and, you may be sure, a large gathering of spectators. The audience, in fact, seemed to spring out of the ground, so suddenly did it appear, and so numerously; In less than a minute there must have been an assemblage of some hundreds—men, women, and children—all crowding round to see the dance.” (Gay, 149).

His Royal Highness arrives in Madras on the early morning of December 13th. He is received at the Royapuram Station by the Governor of Madras, Richard Temple, Duke of Buckingham, with his staff, the civil and military officers, the municipal body and dignitaries of the Presidency, the Rajas of Travancore, Vizianagram, and Cochin, the Nawaz of Arcot, and others. A state procession is set out from the station to the Government House, passing from street to street. A servant holds a golden umbrella over the head of His Royal Highness to relieve the many thousands of residents assembled of any doubt identifying him.

During the days leading up to the Royapuram reception, there are state banquets and visits around the city. His Royal Highness receives the private visits of several Rajahs and chiefs in the audience chamber of the government house. The Maharajah of Travancore, the Maharajah of Cochin, and the Nawaz of Arcot, among many others. One of these visits is of particular interest to me. On December 15th, Vijayamohana Bai, the Princess of Tanjore,2 makes an unannounced visit to the Government House. She is the second daughter of the last rajah of Tanjore, Sivaji, and a surviving representative of the Mahratta Raj of Tanjore. The meeting between the two royals was an unusual one. Since it was uncustomary to look at the face of the Princess directly—only a muslin curtain between two seats could make the meeting possible. The prince could put out his hand for a handshake—but he could not see the Princess’s face. Nonetheless, their exchange was warm and pleasant.3

Entertainment at Royapuram Station

December 17, 1875

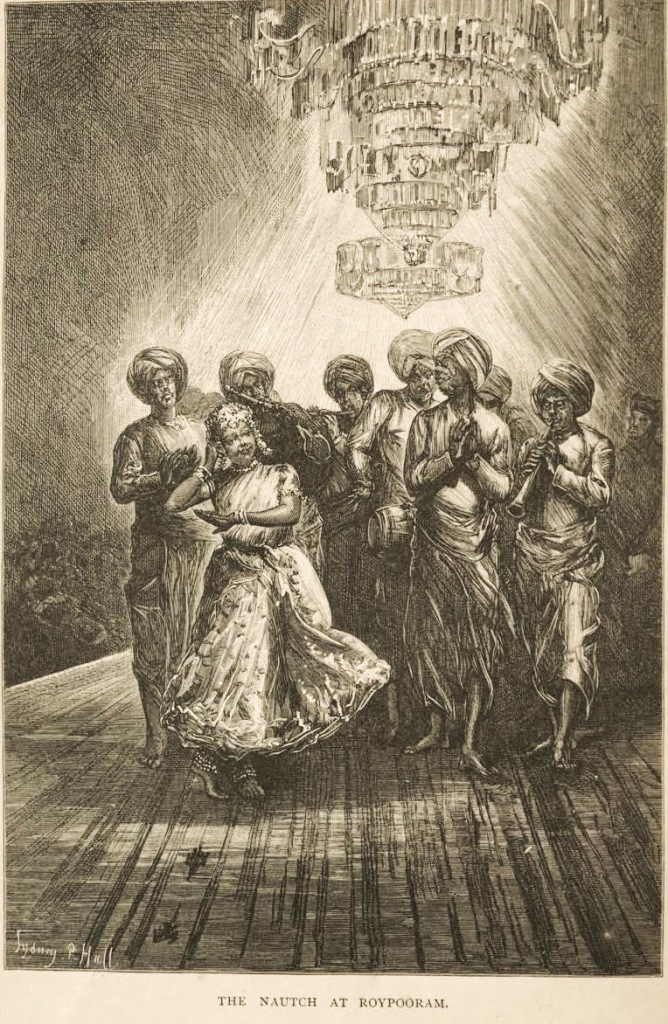

The entertainment in the goods hall of the Royapuram Station must have been, without a doubt, the grandest spectacle one could ever witness. For the occasion, the goods hall was converted into a grand pandal4 that could entertain His Royal Highness and, so it seems, thousands of guests. The walls and tables of the hall were decorated with beautifully arranged flower bouquets, its pillars richly decorated with gold and crimson foil, and fifty magnificent ceiling chandeliers and five electric lights illuminated the goods hall. On the left side, behind muslin curtains, there was a supper room with a refreshment buffet for the special invitees. On the right side center of the hall, an elevated stage was covered with scarlet (red woollen fabric) and ornamented. For the prince and excellencies, there were tilted chairs and one elevation lower, a tier of benches reserved for nobles and other fortunate. The rest of the stage is empty to provide space for entertainment. The remaining guests are to sit or stand around the stage. In the big hall are gathered every rank and style of the presidency of Madras, English and French officers, Princes, chieftains and their entourage from around the country, and hundreds of English residents of Madras, all attired in their best dress. The logistics of the event took a fortnight of careful planning and preparation. The guests needed to be seated appropriately, and all desired to be as close as possible to His Royal Highness. Hundreds of servants and workers must have been part of the event to streamline everything in perfect order.5

The program notes list the entertainment as all artists from Tanjore.

- Music ensemble

- Welcome address

- Pinal Kolattam

- Nautch by the celebrated Gnyana

- Vina with accompaniment

- Pinal Kolattam (2nd act)

- Carnatic vocal ensemble by Krishna

- Sitar with accompaniment

- A drama in four acts

The entertainment is to be from 10 pm to 2 am, but His Royal Highness was held up at a previous engagement and only entered the hall at almost midnight, his arrival announced by music and royal cannon. The prince was seated in the centre of the platform, with his suite directly behind him. Next to the prince on his right side is the Governor of Madras, Richard Temple, the Duke of Buckingham; on the left is the Maharajah of Travancore,6 and the Diwan of Baroda.7 The rest of the chairs were taken by the Maharajah of Vizianagaram,8 and the Nawab of Arcot,9 all glittering in dazzling diamonds, rubies, emeralds, gold, and colourful costumes.

The reception began with a welcome address read out by the chairman of the organising committee. He expressed gratitude at the great honour conferred on the people of Madras by the presence of the Prince at their entertainment. The chairman requested His Royal Highness to accept the exquisite ivory and gold casket, which was placed on a velvet cushion on a small table in front of his chair.10 After the address, well after midnight, the program took off with Pinal Kolattam by about a dozen dancers. They performed in the body of the hall, on a square platform, high enough to be seen from the royal seat. Next was the star of the evening, Gnyana of Tanjore, the only dancer to perform a pas seul.

A Pas Seul by Tanjore Gnyana

It was already far into the night when Gnyana took the stage, but fortunately, the Prince and other royalty remained in their seats to witness her hour-long dance (varnam). From a gangway to the stage, Gnyana entered followed closely behind by her melam. Gnyana’s band of musicians or chinna melam consisted of her nattuvanar and singer, Thiruvarur Periyaswamy, second singer and nattuvan, Thiruvarur Gopala, and Mridangam by Mannargudy Gopalan, with the accompaniment of fiddle, a bagpipe, and a flute player, who added in singing along at some points. From time to time, Gnyana would also sing to emphasise a specific lyric; ceasing her dancing to do so.

—Gnyana wears a rich and heavy podavai in the brightest colours. On her upper arms are armlets of thick gold, richly decorated short and long chains of gold. And in her ears and nose sparkling diamonds. Her thick, shiny hair is braided and set with yellow flowers. She is only eighteen years old when she stands before His Royal Highness and the many other guests, but, Gnyana is confident, pretty, and already a dancer of great repute, even celebrated by the revered Tanjorian nattuvans.

An excerpt from the ‘Queensland Times’, of February 10, 1876, says of her performance:

“First came a sort of prologue, consisting chiefly of salaams to the Prince. Afterwards came a series of slow steps and postures, which left no doubt that Gnyana wished it to be inferred that she was parting from her husband or lover. Then her melancholy deepened, and she was very sad at the absence of the one so near and yet so far. Another figure showed, however, that her lover had returned, and with a lively step she rushed (to meet him) to the feet of the Prince, who could not suppress a smile at her well-expressed ecstasy…Altogether it was a very clever performance, and at its close she was not only loudly cheered, but the Prince sent for her, and thanked her; and the profusion of jewellery about her was examined and admired by the ladies who accompanied his Royal Highness to the fête.”

The description above and other writings of her movements and expressions are enough to assume Gnyana was performing a varnam. But because the Pallavi is not alluded to in any of the publications, it remains unclear which varnam she danced. But I like to believe Gnyana danced the marvellous huseni svarajathi ē mandayānarā and that the prince allowed himself to feel enormous wells of emotion. After the incandescent dancing of Gnyana, His Royal Highness watched a few minutes of the Vina solo before leaving for refreshments in the supper-room, only to return briefly before his final departure from the Royapuram station.

The Life & Times of Tanjore Gnyana

The oral story of Gnyana is provided chiefly by my guru Rajamani. The late Rajamani (-2003), was a student of Panthanainallur Meenakshisundaram Nattuvan and Thanjavur KP Kittappa Nattuvan. I received the details based on two (print) pictures of Gnyana in her possession. For additional information about Gnyana, I spoke with Thanjavur Kittappa in June of 1997. When I gathered the information, my teachers were advanced in age. And although exact memories were blurry, both quite vividly remembered hearing of the famous Gnyana through anecdotal stories narrated by Panthanainallur Meenakshisundaram–he told the stories many times over. Later, in 2003, research historian B.M. Sundaram published his book—Marabu Thantha Manickaangal—in which I found, to an extent, corroboration about the details of Gnyana’s life and times. I have not found any other dancer with the name—Gnyana—who lived towards the end of the 19th century and enjoyed such fame.

Gnyana11 was born in 1857 in Thiruvarur town. Gnyana learnt Sadir from Thiruvarur Ayyaswamy nattuvan, and later from Thiruvarur Periyasamy nattuvan.12 Her maiden performance was at the Thyagaraja temple in 1864/65. In the years that followed, Gnyana became famous for her outstanding abhinaya. According to my teacher, it was not uncommon for dancers to travel from towns to nearby Tanjore and seek out a teacher who belonged to the lineage of the famous quartet brothers (Tanjore Quartet).13 In the 1860s, the repertoire of the brothers was the standard. Gnyana went to learn with Tanjore Mahadevan,14 who was the son of Sivanandam. After her training with Mahadevan and performances in the Tanjore area, Gnyana became known by the honorific ‘Tanjore’ Gnyana.—She danced before the royalty of Tamil Nadu and even foreign royals. She also danced at many wedding receptions or at garden parties of the elite, where she mesmerised the spectators with her expressions.15 For her performances, she received generous remuneration. Gnyana was accompanied by Thiruvarur Gopala nattuvan and Mridanga Mannargudi Gopalan. Panthanainallur Meenakshisundaram (1869-1954) praised her dancing and often went to watch her perform. Gnyana was one of several courtesans who taught the art of abhinaya to the famous nattuvanar Kattumannarkoil Muthukumaran (1874-1960). On special occasions, Gnyana would invite Muthukumaran to perform with her.16 Towards the end of her life, she returned to Thiruvarur, where she died in 1922. Tanjore Gnyana was a celebrated and respected dancer during her lifetime. Every dancer and teacher of those days knew of her.

—

Endnotes

- The Svarajathi “ē mandayānarā nā sāmi” in husánī ragam. The version in praise of the Tanjore Maharajah Pratapasimha (1739-1763), composition of Tanjore Quartet Ponnayya (1804-1864), adapted from the original Magnus Opus of Melattur Veerabhadrayya. ↩︎

- The Princess of Tanjore, Her Highness, Vijayamohana Muktamba Bai (1845-1885), at the time around 30 years of age, is the second daughter of the last Maharajah of Tanjore, Sivaji (r. 1832-1855), and the sole surviving representative of the Mahratta Raj of Tanjore. Rajah Sivaji was the patron of Ponnayya, who composed the svarajathi Gnyana performed at Royapuram. ↩︎

- Princess Vijaya Mohana met Prince Edward with the hope of securing her claim of maintaining the musnud of her forefathers. At the time of the visit, the claim is under favourable consideration before the Madras Government (Hickey, 163. Russel, 327). Earlier, on December 13th, during a stopover of the Prince in Trichinopoly (Trichy), the Maharani of Tanjore, Kamatchi Bai Saheb, presented a belt made of gold as a gift to Alexandra, Princess of Wales. ↩︎

- Canopy or a big tent often used in a religious or other big events that gathers people together. ↩︎

- The Governor of madras, Richard Temple, whose attention to detail resulted in the Madras visit to be successful. ↩︎

- The Maharajah of Travancore, Ayilyam Thirunal, Reign: 1860-1880. ↩︎

- Sir Mahadeva Rao Thanjavurkar, the Diwan of Baroda from 1875-1882. ↩︎

- The Maharajah of Vizianagaram, Pusapati Ananda Gajapati Raju, Reign: 1850-1897. ↩︎

- The Nawab of Arcot, Saheb Zahir-ud-Daula Bahadur Reign: 1874-1879. ↩︎

- The people of Madras presented the welcome address in a casket known as—The Madras Casket—specially designed as a gift for the Prince. The casket was a combination of ivory and gold, measuring 18” x 7” x 5”, with at each corner a slab of ivory of 20” x 9” x 1” are four tigers couchant, supporting the casket, which is also of ivory, overlaid with a rich network of embossed gold work. On the front of the casket is an inscription in gold letters; it reads, Presented to H. R. H. The Prince of Wales, by the people of Madras, 1875. Surrounding this is a troop of dancing girls and musicians, illustrating scenes in the life of Krishna. Another illustration is of Mahadeva with the Ganges flowing from the crown of his hair. Other deities, Brahma, Vishnu, Shiva, and Kali, are also depicted. Captain Kenny Herbert designed the casket. The total value of the gift around 460 pounds. ↩︎

- Gnyana is also spelled as Gnanam or Gnanamammal. Either way is correct. Gnanamammal would indicate of having crossed 50 years of age. ↩︎

- According to historian, BM Sundaram, Gnyana, from the age of three, learnt the basic adavus from Ayyaswamy. Later she joined Thiruvarur Periyaswamy nattuvanar, and after four years she did her Arangetram at Thyagarajaswamy temple. After a few years, she went to Tanjore to study with Tanjore Mahadevan. ↩︎

- Chinnayya (1802-56); Ponnayya (1804-1864); Sivanandam (1808-1863); Vadivelu (1810-1847). The brothers reimagined Tanjore court dance and created a standard courtesan repertoire, later known as Margam. ↩︎

- Nattuvanar Mahadevan II (1832-1904) was the son of Tanjore Quartet, Sivanandam. Gnyana may have also studied the svarajathi with the famous Bhagavata Sulamangalam Seetharama Bhagavatar. ↩︎

- In another anecdote of my teacher, Rajamani (told to her by Meenakshisundaram), Gnyana was invited to dance at the garden parties of Britishers, where she danced the famous varnam sarasālanu ipudu marimānarā (Kapi, Tanjore Ponnayya). ↩︎

- Kattumannarkoil Muthukumaran was the dance master of famous dancers, Mrinalini Sarabhai, MK Saroja, Ram Gopal, Rukmini Devi Arundale, Kamala Laxman (Kumari Kamala). ↩︎

Oral Informants

My Gurus: Rajamani (d. 2003); Thanjavur K.P. Kittappa nattuvanar (1913-1999); Panthanainallur M. Gopalakrishnan nattuvanar (1938-2015). And additional informants: Panthanainallur C. Subbaraya nattuvanar (1914-2008) and his disciple the late Nirmala Ramachandran.

Bibliography:

Fayrer, J. 1879. Notes of the Visits to India of their Royal Highness the Prince of Wales and Duke of Edinburgh, 1870 – 1875/6. Nearby & Endean, London.

Gay Drew J. 1877. The Prince of Wales in India. R. Worthington, NY.

Hickey, William. 1874. The Tanjore Mahratta Principality in Southern India. 1st edition.

Hirschfeld, J. 2008. The Tanjore Quartet & the Maharajahs of the Tanjore Musnud as the Patrons of Dance. Access on academia.edu.

Kittappa, K. P. 1961. The Dance Compositions of the Tanjore Quartet. Ahmedabad: Darpana Publications.

Russel, William Howard. 1877. The Prince of Wales’ Tour: A Diary in India. Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, London.

Sundaram, B.M. 1997. Towards a Genealogy of Some Tanjavur Natyacharyas and their Kinsfolk. Sangeet Natak 124: 30–41..

———. Marabu Thantha Manickaangal. 2003. Dr V. Raghavan Centre of Performing Arts, Chennai.

Wheeler, G. 1876. India in 1875-1876, The visit of the Prince of Wales. Chapman, and Hall, 193, Piccadilly.

The Illustrated History of the British Empire in India and the East, from the earliest times to the suppression of the Sepoy Mutiny, Virtue, London, 1878-79.

Reviews ‘Queensland Times’, of Thursday, February 10, 1876 (and numerous other newspaper clippings).

Also Read

COPYRIGHT

All Rights Reserved © 2006-2016

“Courtesan Tanjore Gnyana, A Pas Seul at Royapuram,

Madras, December 17, 1875”

By Jeetendra Hirschfeld

Sathir Dance Art Trust

Amsterdam-Chennai

The content of this essay, text, photo and videos

is for private use alone, unauthorised publication in any form,

is prohibited without the prior written permission of the author.

Thank you for this insightful research work. Never knew about thos dancer.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Remarkable historical event. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person